By Dr. Corinne Masur

For those of you who have children in middle school, Jr. High and High School, what do you think about trigger warnings?

Should kids be warned before they are assigned a book with content that might cause them some upset?

Or is it the role of schools (and colleges) to expose kids to all kinds of ideas and descriptions of all sorts of events?

And for that matter, is teaching the history of various wars worthy of a trigger warning (violence! death!) any less than teaching The Scarlet Letter or Madam Bovary (adultery!) or The Kite Runner (sexual violence!).

Is it the job of educational institutions to help kids to learn how to think about even upsetting subjects?

This brings us to the subject of trauma.

Trauma is a word that is used carelessly these days. Almost anything can be called a trauma. But what trauma really is is an event that is utterly overwhelming to an individual, the effects of which can be lasting.

So what do we do for kids who have been exposed to truly traumatic events in their own lives? Do we owe them a trigger warning so that they are not surprised – or triggered – when material comes up in class or in an assignment that reminds them of their own experience?

These are very difficult questions.

And it is easy to see each side:

We do not want to intentionally re-traumatize kids.

At the same time we DO want to teach them how to think about and talk about the upsetting things that have happened over the history of the world, that are written about in world literature and that are continuing to happen every day in our current world.

There are no trigger warnings in life, after all.

Recently, this issue was taken up by Cornell University when a group of students asked for trigger warnings to be routinely provided in class. The results of the debate may surprise you.

See below for an excellent article on the topic from The New York times:

Should College Come With Trigger Warnings? At Cornell, It’s a ‘Hard No.’

When the student assembly voted to require faculty to alert students to upsetting educational materials, administrators pushed back.

At Cornell University, the undergraduate student government wanted to require instructors to warn students about potentially traumatic course material. (Credit Heather Ainsworth for The New York Times)

By Katherine Rosman | April 12, 2023

Last month, a Cornell University sophomore, Claire Ting, was studying with friends when one of them became visibly upset and was unable to continue her work.

For a Korean American literature class, the woman was reading “The Surrendered,” a novel by Chang-rae Lee about a Korean girl orphaned by the Korean War that includes a graphic rape scene. Ms. Ting’s friend had recently testified at a campus hearing against a student who she said sexually assaulted her, the woman said in an interview. Reading the passage so soon afterward left her feeling unmoored.

Ms. Ting, a member of Cornell’s undergraduate student assembly, believed her friend deserved a heads-up about the upsetting material. That day, she drafted a resolution urging instructors to provide warnings on the syllabus about “traumatic content” that might be discussed in class, including sexual assault, self-harm and transphobic violence.

The resolution was unanimously approved by the assembly late last month. Less than a week after it was submitted to the administration for approval, Martha E. Pollack, the university president, vetoed it.

“We cannot accept this resolution as the actions it recommends would infringe on our core commitment to academic freedom and freedom of inquiry, and are at odds with the goals of a Cornell education,” Ms. Pollack wrote in a letter with the university provost, Michael I. Kotlikoff.

To some, the conflict illustrates a stark divide in how different generations define free speech and how much value they place on its absolute protection, especially at a time of increased sensitivity toward mental health concerns.

After decades of university battles over tinderbox issues of students’ rights, speech codes and how best to grapple with unpopular speakers and ideas, proponents of free speech are lauding Ms. Pollack’s quick and unequivocal action. They characterize it as part of a larger national shift, marked by university leadership more forcefully pushing back against efforts to shut down speakers and topics that might offend.

“What was unique about the Cornell situation is they rapidly turned in a response that was a ‘hard no,’” said Alex Morey, the director of campus rights advocacy for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a nonpartisan organization focused on issues of free speech. “There was no level of kowtowing. It was a very firm defense of what it means to get an education.”

Martha E. Pollack, the president of Cornell University, said the student resolution concerned her because it could impinge upon the freedom of faculty to select material and present it as they think is most beneficial. (Credit Heather Ainsworth for The New York Times)

Ms. Morey called it the “Stanford Effect,” referring to a 10-page open letter written in March by Jenny Martinez, dean of Stanford University Law School, in which she affirmed her decision to apologize to Stuart Kyle Duncan, a Donald J. Trump-appointed federal appeals judge, after hecklers interrupted his speech.

Earlier this month, Neeli Bendapudi, the president of Pennsylvania State University, released a four-minute video explaining why she believed a public university like Penn State had a legal and moral obligation to host speakers who espouse views that many may find abhorrent. “For centuries, higher education has fought against censorship and for the principle that the best way to combat speech is with more speech,” she said.

The current free speech issue at Cornell is one that has been debated on campuses across the country. “Content warnings” or “trigger warnings” refer to verbal or written alerts that assigned material, including academic writing or artistic expression, may involve sensitive or upsetting themes or details that may cause a student to have an emotional response tied to a personal experience.

Professors on some campuses use such warnings, though mandates are rare.

At Cornell, the students’ proposal suggested that the warnings be issued when course readings and discussions involved topics “including but not limited to: sexual assault, domestic violence, self-harm, suicide, child abuse, racial hate crimes, transphobic violence, homophobic harassment, xenophobia.”

It stipulated that “students who choose to opt out of exposure to triggering content will not be penalized, contingent on their responsibility to make up any missed content.”

To Ms. Ting and other proponents of the measure, including the woman in the Korean American literature class, the administration’s swift rebuke was frustrating. “We have been characterized as triggered snowflakes,” said Shelby L. Williams, a sophomore who co-sponsored the resolution. “What we are asking for is greater context.”

The concept of trigger warnings first entered the cultural dialogue in the post-Vietnam War era, after post-traumatic stress distress disorder became a recognized health condition. PTSD episodes, which include rage and anxiety, are generally triggered by places, people, sounds or smells reminiscent of a traumatic experience, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Integrating trigger warnings into academia first took root in the 1990s but gained urgency after the #MeToo movement opened a dialogue about trauma. A study published in 2019 in the Journal of American College Health said 70 percent of college students report that they have been exposed to at least one traumatic event.

Students with diagnosed PTSD are entitled to care from universities and should be treated by trained professionals, said Amna Khalid, a professor of history at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., who has been writing and speaking about campus culture since 2016.

But, Professor Khalid said, addressing students’ mental health issues through trigger warnings is ineffective. It disempowers people by reducing their identities to traumatic events and “infantilizes” students whom professors should be preparing for adult life, she said.

“Life happens to you while you are driving, while you are walking, while you are in the supermarket,” she said. “The most challenging moments in life rarely come with warning.”

Professor Khalid called trigger-warning mandates an infringement on the academic freedom of professors whose role is to help students develop critical thinking skills.

“Sometimes that requires surprising them and challenging them in ways that are uncomfortable,” she said. “It diminishes the learning experience for students if professors hedge themselves.”

Some professors support the use of trigger warnings. “When used correctly,” said Connor Strobel, a professor of social sciences at the University of Chicago, “trigger warnings can open up a conversation” with students, enabling professors to alert them to available resources.

Professor Strobel recently asked students to read “The Second Sex,” by Simone de Beauvoir, and alerted them that the book included themes of “menstruation and menopause, and things that women are shamed for,” he said.

One student approached him and said that because of a family issue, she was concerned about reading it. He was willing to create an alternate assignment for her but first encouraged her to start the book and see if she found it more compelling than upsetting. “She found it very salient,” he said, and completed the assignment.

“At a university, there is no topic that should be off the table, but trigger warnings are a preview of coming attractions that treat students with humanity,” he added.

When Professor Strobel was a graduate student at University of California Irvine in 2016, he wrote a proposal asking a faculty government association to endorse the use of trigger warnings on campus.

That document became an inspiration for Ms. Ting’s Cornell resolution.

The Cornell measure was publicized by The Cornell Daily Sun, the student newspaper, and kicked up a conversation on Twitter. Normally, Ms. Pollack, the university president, takes about a month to weigh in on student assembly proposals. But in this case, she responded in just a few days.

The resolution concerned her, she said in an interview, because it could impinge upon the freedom of faculty to select material and present it as they think is most beneficial.

She also believes a rule that codifies the avoidance of upsetting topics runs contrary to the role of a university.

“Our students are coming at this with good intentions,” Ms. Pollack said, “but I think it’s a critical part of higher education to learn how to engage with challenging and difficult ideas. It teaches you to listen, compromise and advocate.”

It was the first assembly measure of more than 30 this academic year that the president has rejected.

Lee Humphreys, chair of the communication department at Cornell, was pleased by Ms. Pollack’s response.

In the past, she has presented her classes with violent, sexual and distasteful content to push students to consider who might be drawn to the programming and who might financially benefit from it.

“If I was really concerned about making sure I was covering all of my bases in terms of trigger warnings, it would make my life easier to not show the kind of content in the class that I would otherwise show, just in case there was something that I was overlooking,” Professor Humphreys said. “I think that’s doing a disservice to the class and the students, to avoid things that are difficult.”

Professor Humphreys often previews for students what is to come in a lesson, as a part of “reinforcing pedagogical goals,” she said, and aims to be sensitive to students.

“Just because you don’t support a mandate doesn’t mean that you don’t support an inclusive learning environment,” she said.

Students had a mixed reaction to the resolution, with the conservative student newspaper, The Cornell Review, calling it “an embarrassment” in an editorial published last week. “Hiding from ideas is no less than intellectual cowardice. It’s exactly the opposite of what this country needs,” the paper said.

Cullen O’Hara, a Cornell University senior, is the co-editor-in-chief of the Cornell Review, a conservative student paper, which has editorialized against the content warning proposal. (Credit Heather Ainsworth for The New York Times)

Cullen O’Hara, co-editor-in-chief of The Review, said that the editorial board did not believe the student assembly represented a majority of students and saw the resolution as endemic of broader free speech issues.

“We are very opposed to trigger warnings which we think would chill the discussion in classrooms, which we already believe are one-sided,” said Mr. O’Hara, a senior.

The student assembly will discuss the trigger-warning resolution with the administration on Thursday, at a previously scheduled meeting between Ms. Pollack and the assembly.

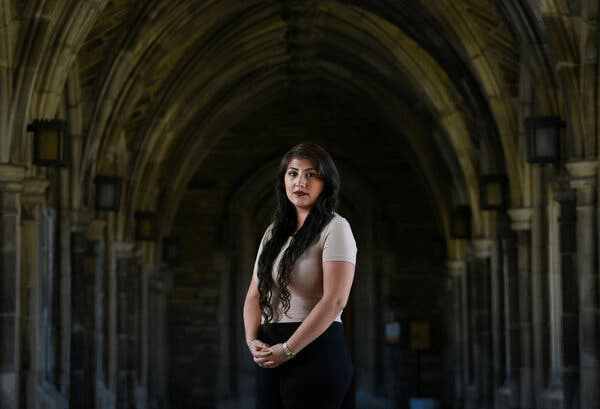

“I think the response is purposeful in focusing on the wrong part of the resolution,” said Valeria Valencia, a senior and the Cornell University Student Assembly president, “turning it into an issue of academic freedom and not one of protecting students, when both things can coexist.”

Valeria Valencia, a Cornell University senior and president of the student assembly, supported the resolution on content warnings. (Credit Heather Ainsworth for The New York Times)

Ms. Ting, the writer of the resolution, said she is considering amending the proposal. “But first I want to do more due diligence and reach out to faculty and administration to see how we can find the right balance,” she said.