When I was a child I never won anything. I mean never. I went to an academically competitive school and while I suppose I was smart, evidently I wasn’t smart enough to win any awards.

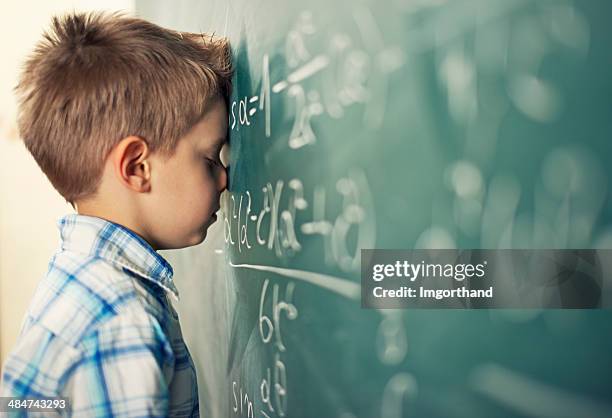

This was in an era, long ago, when it had not yet come into vogue to tell children they were doing a good job. My school was big on telling children they were not trying hard enough.

Often, my parents were told that I was not living up to my potential. And once, my mother was told that I always sat in the back row – and this was in a classroom that only had two rows. This kind of feedback was crushing to my self-esteem, not to mention other aspects of my self-confidence.

It made me feel badly about myself. And you could easily think that this was destructive. However, what actually happened is that it made me mad, really, really mad. And I decided to show them. In high school, I got interested in psychology and in theories of education. I decided I could understand and help children in a way that I had not felt helped or understood. I went to a college that was as different from my high school as possible. It was a wonderful antidote. And then it went bankrupt. I had to find another college. And then I had to convince that new college to accept the credits from my beloved and highly non-traditional, now defunct, former school. Then I decided to go to graduate school to get a doctorate, something the director of studies at my high school would not have predicted. I didn’t succeed the first year. I didn’t succeed the second year. I had to try three years running to get into a program I wanted to go to.

If I wasn’t as “smart” as the kids who had won the awards early in my school career, at least I had perseverance.

And then, at a time when psychologists were not allowed to enter clinical psychoanalytic training at most institutes, I decided I wanted to become a psychoanalyst. Of course.

I say all this for a purpose. Telling kids they are doing a good job is now in fashion. Shielding children from criticism, protecting them from failure and helping them to feel they have succeeded is something parents routinely do. But it is important to keep in mind that motivation and drive do not necessarily come from a lifetime of success. And success is not defined by always succeeding, or by a life lived without suffering.

Henri Parens, a child psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor, revamped the psychoanalytic theory of aggression. He wrote that aggression comes from an overabundance of frustration. But he also said that there are two kinds of aggression: hostile, destructive and non-hostile, non-destructive. And, it turns out that this latter type of aggression is what motivates us to move forward in life. We need SOME aggression to motivate us. And we need SOME frustration, in addition to our inborn, natural aggressive impulses, to generate that motivation.

So, frustration is necessary for children. Some frustration can lead to a feeling of wanting to do better next time. Shielding children from experiences of frustration and even occasional failure is not beneficial. And telling kids that they have done a good job when they actually have not is not helpful. Kids need to feel motivated by not doing well sometimes and the frustration that comes from that in order to want to try again and try harder.

If you have any doubt about this, read Ernst Papanek’s Out ofthe Fire about the hundreds of children he housed and educated during the early days of World War II in France. These children were separated from their families; some walked across Europe, some went from hiding to hiding until they reached one of Papanek’s homes for children. And what did those who survived become? They became lawyers and doctors and writers and professors.

Winners are not people who do not lose – or suffer – they are people who keep trying.