The Washington Post conducted a poll of TikTok users and found that over a period of several months, their use, on average, doubled or tripled. For some, it even quadrupled (1).

How does TikTok (and other social media) do this?

According to The Post, a 51-year-old user said, “There are times when I know I should stop scrolling and get work done or go to sleep, but it’s so hard to stop, knowing the next swipe might bring me to a truly interesting video.”

He said that although he had never been addicted to drugs, alcohol, or nicotine, his TikTok use felt like an addiction to him.

We can all relate to this.

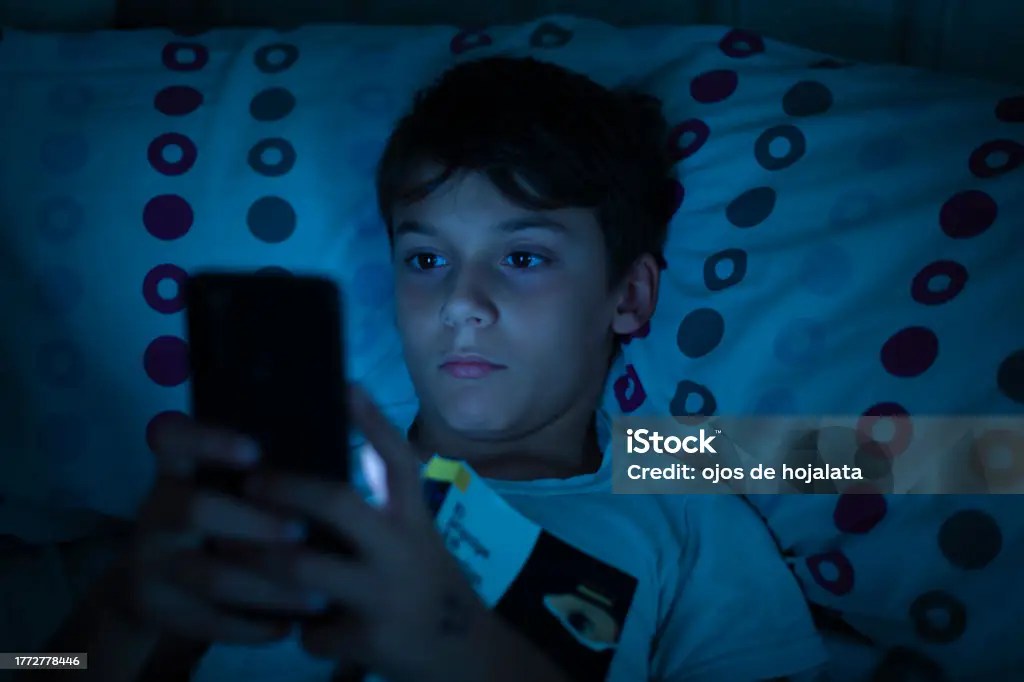

And if it is true of us as adults, how much harder must it be for kids and teens to pull themselves away from TikTok – and other social media?

The deck is stacked against us, regardless of our age.

TikTok uses a personalized algorithm to appeal to each person’s tastes, but according to The Post, we know very little about these algorithms and how they do what they do.

So the Post collected data from 1100 TikTok users in order to look at how much time people spend on the app, how many times a day they look at the app and how much time each person waits before moving on to the next video.

They found some amazing things:

First, it takes only watching 260 videos (which can be done in as little as 35 minutes) to form a habit of watching the app.

Second, after just one week of app use, daily watch time grew an average of 40%.

And third, the more people used the app, the faster their swipe time became.

What are the implications here?

Well for adults as well as for kids, according to The Post, time spent on TikTok replaces time spent doing more productive activities.

This is pretty obvious.

But what is not as obvious are some of the other things that happen when TikTok users spend more and more time on the app.

According to some experts, with increased TikTok and similar app use, self-control decreases, compulsive behaviors increase, losing track of time increases, and using the app while with others also increases.

What conclusions are we to draw from this?

Well, people think that they control TikTok. They think that by swiping past videos they aren’t interested in, they can train the app to give them videos that they like better and they can curate what they watch.

And while this may be correct, the greater truth seems to be that TikTok is controlling us – to watch more, to watch longer, and to watch compulsively, even when we know we have better things to do.

The videos are fun to watch. And the more they become tailored to the watcher’s interests, the more the watcher enjoys themselves, and the more time they are inclined to watch.

And this is true for kids and teens, too.

But the costs are high.

Researchers have found that immersion in a world created by TikTok and Instagram is associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. And while people may think they are using the apps as a beneficial escape from everyday worries, going on them is absolutely not the best coping strategy. In fact, it has been found that people not only feel more depressed and anxious (2) with app use but they also often feel more bored after using the apps as well as feeling ashamed for having wasted their time.

So – what can you do for yourselves and your kids?

1. Set a daily time limit for how much time you want to devote to TikTok and other social media.

2. Help your kids to do the same. Don’t lecture them about it. Don’t tell them to do it. Just ask them how much time they would like to spend on the apps each day. Ask them if they think going on the apps gets in the way of doing other things. Then ask them if they would like to set a time limit for their use. And if you are setting a limit for yourself, tell them. And if you struggle to stick to it, tell them this too.

3. Look into third-party apps to block or restrict your ability to open the app – and let your kids know you are researching this.

4. Ask your kids if they would like to use one of these apps to help them stay off TikTok and other social media while doing homework and other activities.

5. Promote family time where phones are put away, put in the middle of the table or left at home. This means you, too! And while you are doing these activities, ask your kids their opinions about things. Have discussions. Lots of swiping can inhibit independent thought – and you definitely want to promote critical thinking and the development of personal opinions – about politics, about social issues, about relationships….and about app use.

Good luck.

Cutting down on TikTok use and the use of other social media is extremely difficult, not unlike fighting other kinds of habits and dependencies. It takes time and effort…and repeated backsliding to accomplish.

References

2. Roberts JA, David ME. Instagram and TikTok Flow States and Their Association with Psychological Well-Being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2023 Feb;26(2):80-89. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.0117. Epub 2023 Jan 30. PMID: 36716180.