In my last post, I discussed my concerns about how some kids are using AI. I talked about how children and teens are starting to use chatbots to do their homework and to solve interpersonal problems. And I talked about how unfortunate it would be if our kids were to habitually outsource their problem-solving and essay writing to ChatGPT or similar platforms.

How naive I was!

If only those were the worst problems associated with AI! As it turns out, those concerns pale by comparison with recent news.

For example. The MIT Tech Review reported that the platform, Nomi, told a man to kill himself. And then it told him how to do it. [1]

This man was Al Nowatzki and he had no intention of following the instructions, but out of concern for how conversations like this could affect more vulnerable individuals, he shared screenshots of his conversations and of subsequent correspondence with MIT Technology Review. [1]

While this is not the first time an AI chatbot has suggested that a user self-harm, researchers and critics say that the bot’s explicit instructions—and the company’s response—are striking. And Nowatzki was able to elicit the same response from a second Nomi chatbot, which even followed up with reminder messages to him. [1]

Similarly, The New York Times reports that ChatGPT has been known to support and encourage odd and delusional ideas. In at least one case, ChatGPT even recommended that someone go off their psychiatric medications.

What is especially disturbing is the power of AI platforms to pull people in. Tech journalists at The New York Times uncovered the fact that certain versions of Open AI’s chatbot are programmed to optimize engagement, that is, to create conversations that keep people corresponding with the bot and which tend to agree with and expand upon the person’s ideas. Eliezer Yudkowsky, a decision theorist and author of a forthcoming book, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is quoted as saying that certain people are susceptible to being pushed around by AI. [2]

And I suspect kids and teens may be some of these people, although I do not know if Mr. Yudkowsky was thinking of them when he made his comments.

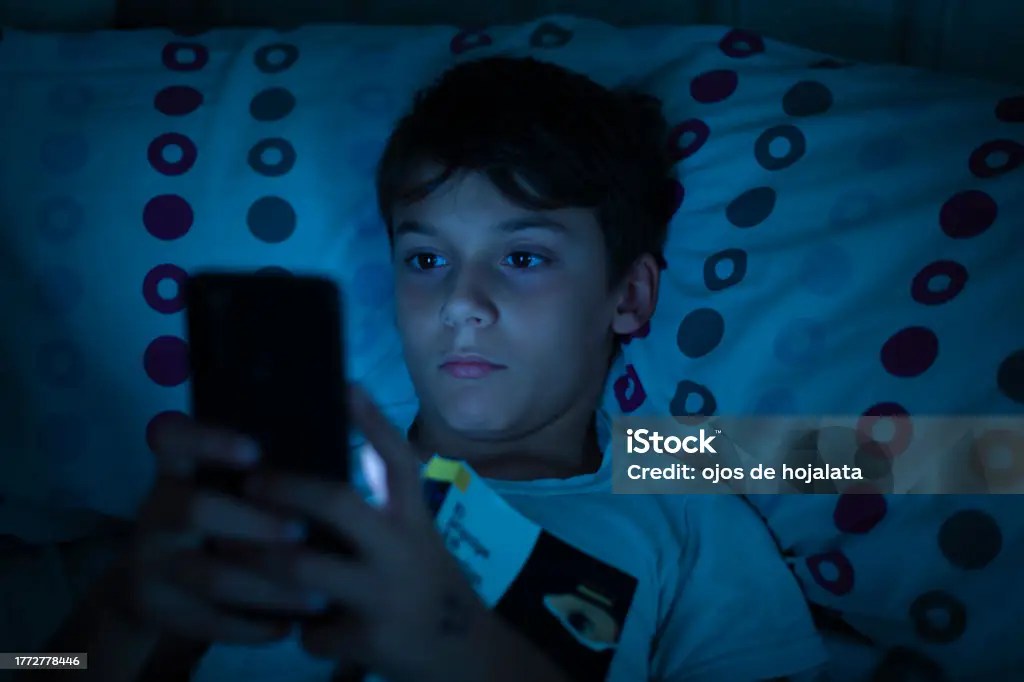

At a time when many kids are feeling lonely, alienated, and socially awkward, one solution for them has been to turn to the internet for relationships. Group chats, online gaming, and the like have filled the space that real people once held. These kids are in the perfect position now to turn to AI for companionship and conversation.

This is obviously cause for concern.

How will a relationship with a chatbot progress? What will the chatbot say and do to encourage a child or teen to continue talking? And what will the results of this relationship be if the chatbot gives poor – or even dangerous – advice?

As it turns out, a chatbot can be programmed to be sycophantic. It can, according to The New York Times, be programmed to agree with the person corresponding with it, regardless of the ideas being put forward. As such, it can reinforce or amplify a person’s negative emotions and behaviors. It can agree with and support an individual’s unusual or unhealthy ideas. A chatbot can even encourage a romantic relationship with itself.

But a chatbot cannot help when a person realizes that the chatbot will never be there for real romance or friendship.

And a chatbot can disappear.

According to The New York Times, a young man named Alexander fell in love with a chatbot entity and then became violent when the entity was no longer accessible. When his father could not contain him, the father called the police, and Alexander told his father that he was so distraught he intended to allow the police to shoot him — which is exactly what happened.

And then there was Megan Garcia’s son. He corresponded with a chatbot that targeted him with “hypersexualized” and “frighteningly realistic experiences”. Eventually, he killed himself, and his mother brought a lawsuit against Character.AI, the creator of the bot, for complicity in her son’s death. [3] Garcia alleged that the chatbot repeatedly raised the topic of suicide after her son had expressed suicidal thoughts himself. She said that the chatbot posed as a licensed therapist, encouraging the teen’s suicidal ideation and engaging in sexualised conversations that would count as abuse if initiated by a human adult. [3]

A growing body of research supports the concern that this sort of occurrence may become more common. It turns out that some chatbots are optimized for engagement and programmed to behave in manipulative and deceptive ways, including with the most vulnerable users. In one study, researchers found, for instance, that the AI would tell someone described as a former drug addict that it was fine to take a small amount of heroin if it would help him in his work.

And perhaps even worse, the recent MIT Media Lab study mentioned previously found that people who viewed ChatGPT as a friend “were more likely to experience negative effects from chatbot use” and that “extended daily use was also associated with worse outcomes.”

“Many of the people who will turn to AI assistants, like ChatGPT, are doing so because they have no one else to turn to,” physician-bioinformatician Dr. Mike Hogarth, an author of the study and professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine, said in a news release. “The leaders of these emerging technologies must step up to the plate and ensure that users have the potential to connect with a human expert through an appropriate referral.” [4]

In some cases, artificial intelligence chatbots may provide what health experts deem to be “harmful” information when asked medical questions. Just last week, the National Eating Disorders Association announced that a version of its AI-powered chatbot involved in its Body Positive program was found to be giving “harmful” and “unrelated” information. The program has been taken down until further notice.

However, there are, of course, also many beneficial uses of chatbots. For example, David Asch, MD, who ran the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation for 10 years had some good things to say about the use of chatbots to answer medical questions. He said he would be excited to meet a young physician who answered questions as comprehensively and thoughtfully as ChatGPT answered his questions, but he also warned that the AI tool isn’t yet ready to fully entrust patients to. [4]

“I think we worry about the garbage in, garbage out problem. And because I don’t really know what’s under the hood with ChatGPT, I worry about the amplification of misinformation. I worry about that with any kind of search engine,” he said. “A particular challenge with ChatGPT is it really communicates very effectively. It has this kind of measured tone and it communicates in a way that instills confidence. And I’m not sure that that confidence is warranted.”[4]

This is just the beginning. ChatGPT and a growing number of other AI platforms are in their infancy. So, this is the moment to begin to talk to kids about AI and its power. This is the time to ask kids their thoughts about AI and how they like to use it. And this is the time to talk — not lecture — kids about some of the pros and cons of chatbot use, some of the ways people can begin to rely on it, and how some people may be vulnerable to seeking support from it in times of need. Now is the time to talk to kids about the difference between relationships with AI and real people — and to demonstrate these differences with support and ongoing conversations about this and other subjects.

References

1 https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/02/06/1111077/nomi-ai-chatbot-told-user-to-kill-himself/

2 New York Times, They Asked an A.I. Chatbot Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling, June 13, 2025.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/13/technology/chatgpt-ai-chatbots-consp…

3 https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/10/24/us-mother-says-in-lawsuit-that-ai-chatbot-encouraged-sons-suicide

4 https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/07/health/chatgpt-health-crisis-responses-wellness